The "better Prime Minister" or "better Premier" score in Newspoll polling is a frequent subject of media focus. This article explores the history of Newspoll preferred leader scores at state and federal elections and during terms and finds that:

* Better Leader scores are skewed indicators that favour incumbents by around 14-17 points at both state and federal level.

* Better Leader scores add no useful predictive information to that provided by a regression based on polled voting intention.

* If anything, Prime Ministers with high Better Prime Minister leads may be more likely to underperform their polled voting intention, but this is already captured in the relationship between polled voting intention and actual results.

* At state level, leading as Better Premier is a worse predictor of election wins or losses than leading on two-party preferred and having a positive net satisfaction rating. This is because Better Premier is a weaker predictor of vote share than polled 2PP and is also more skewed as a predictor of election outcomes than either.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

With the coronavirus outbreak having postponed elections in my own state, shut down election review committees and generally reduced media and political interest in electoral matters, there's not too much to do on here right now. So I might take the opportunity to look back at some themes of interest that I covered in the earlier days of this site and see if they still hold up with the addition of fresh data. (A note that this particular article is fairly number- and graph-heavy and has been graded 4/5 on the Wonk Factor scale.)

The first piece up for a revisit is an article written way back in 2012, in the very early days of this site, called Why Preferred Prime Minister/Premier Scores Are Rubbish. Unlike most articles here, this article's popularity rose several years after it was released, especially in the last twelve months of the 2016-2019 term. But that article was written three elections and, sigh, four Prime Ministers ago. It was also written at a very particular time - in late 2012 the Gillard government had a short-lived resurgence in polling and appeared competitive, before collapsing again in early 2013. This article is written to complement the earlier article and not to completely rewrite it, so I haven't touched on some themes covered in depth in the earlier piece (such as the fact that Better PM scores don't tell you if anyone actually likes either leader.)

Has the 2019 election, at which the Newspoll "Better Prime Minister" won but the Newspoll voting intention leader lost, breathed new life into Better PM scores as a useful predictor? The short answer is not really. And because there aren't so many federal data points to look at I thought I'd use state elections as well to see if they said anything more promising about Better Premier scores. The answer there is no as well.

The Better Prime Minister score (often called "preferred" Prime Minister, but both Newspoll and Essential use "better") is a frequent object of media interest when new polls are released. The Australian frequently leads off with it rather than the approval ratings of specific leaders in its online coverage. The standard question form is "Who do you think would make the better Prime Minister?" and the available alternatives are the Prime Minister, the Opposition Leader and, usually, some kind of uncommitted/don't know response. (ReachTEL platform polls have often used a forced choice between the two leaders.) Better PM scores are the subject of a lot of spinning from pundits who believe they hold a secret key to understanding what is really going on.

Yet the history of Better Prime Minister as an indicator of anything but a vacuous form of political "beauty contest" has long been weak. In 1993 Paul Keating trailed John Hewson by a point on election eve and won. In 1996 John Howard trailed Paul Keating by five points and beat him. Better PM failed for a third election in a row in 1998 when Howard trailed Kim Beazley by a point and won again, albeit without winning the two-party preferred vote (2PP). Other predictive fizzers for the Better Prime Minister score taken at face value have included 1990, 2010 and 2016 (BPMs lopsided, elections close) and 2007 and 2013 (BPMs close, elections lopsided).

In 2007 the Australian went all-in and lost on an argument that close Better Prime Minister scores meant John Howard was in with a real shot against Kevin Rudd, complete with the immortal claim that "we understand Newspoll because we own it". In fact The Australian did not understand that Better Prime Minister was an indicator that usually skewed to incumbents.

The term "rubbish" may seem harsh given that I frequently comment on Better PM scores, records and so on. However the overwhelming evidence is that Better PM scores are a distraction that do not assist in measuring how governments are going, and that they should not be so prominently highlighted given the severe difficulty of working out what they actually mean.

What predicts results: voting intention, the PM's own ratings or Better PM?

If Better PM was a useful indicator then it might either outperform standard voting intention, or at least add value to a voting intention based predictor, so that knowing both the polled voting intention on election eve and the Better PM result made it much easier to predict the election.

Of the 12 Newspoll-era elections, the candidate ahead as Better PM has won nine and lost three. That doesn't sound too bad, but it is also the case that the government of the day has won nine and lost three. The party ahead on the released 2PP has won eight and lost three, which also becomes 9-3 if the 2004 Newspoll is adjusted to use previous-election preferences (the poll was using respondent preferences, which didn't work very well). However, a rule more consistent with the history of governments that lose the 2PP narrowly retaining office would be that if the government is polling at least 49% 2PP it wins, otherwise it loses: that method would score 10 correct predictions with two wrong (1998, 2019).

Because just predicting wins and losses is very granular, it's more useful to look at how well different indicators predict the two-party preferred vote. And in this respect, unsurprisingly, the best predictor of voting results has been voting intention. But there's a slight catch here - voting results are a better predictor if you take into account a history of the trailing party often doing better than the final Newspoll says.

Here's some graphs comparing the final Newspoll 2PP, the final Newspoll PM net rating and the final Newspoll Better PM lead for the incumbent as predictors of the actual 2PP. Where Newspoll did not publish a 2PP I have calculated one using previous-election preferences.

In all cases there's a positive correlation, but it's much stronger in the case of voting intention, with 44% of variation explained (it was 54% before 2019) with the other two explaining less than a quarter. In the case of PM netsat and Better PM lead, these relationships are not even statistically significant after 12 elections! But also, Better PM is a skewed indicator. All else being equal, a government polling 50% 2PP does get about 50% 2PP. A government whose PM has as many people satisfied as dissatisfied with their performance also gets 50% 2PP. But on average a PM needs a Better PM lead of 13.6 points to get a 50% 2PP on election day.

Does Better PM Help Fill In The Gaps?

It would be useful if Better PM still added some predictive information to the stronger indicator of voting intention when it came to predicting 2PP results. Perhaps a strong Better PM lead would be a useful sign that the voting intentions polling was off the show as it was in 2019? Well no - in fact, if anything, the opposite:

In the last 12 federal elections, the higher Better PM leads have been correlated with governments underperforming compared to their final 2PP polling, and small leads and deficits have been correlated with governments overperforming. This is actually weakly statistically significant at p<.05 level if last-election preferences are used instead of Newspoll's published 2PP for 2004 - but treat that with caution because of the number of different tests I am doing in this article. Also, this relationship either doesn't apply or applies very weakly at state level.

Assuming the negative relationship is a thing, it is probably because (and see the "Polled vs Actual 2PP" chart above) federal results are on average closer to 50:50 than final polls anticipate, and high 2PP leads tend to come with high Better PM leads (perhaps as a result of inaccurate sampling). But it is also possible that high Better PM leads, even a few days out from elections, indicate that a government is carrying soft supporters who may switch their vote when they think about policy instead of leadership. (This is a version of Peter Brent's theory that for a given set of voting intentions, it is better to have a bad approval rating than a good one, but it seems to actually work better for Better PM federally than it does for net satisfaction.)

Multiple regression with two variables and only 12 elections is a bit risky, but for what it's worth, a multiple regression with polled 2PP and Better PM lead only increases the percentage explained to 45.4% (from 43.8% with just polled 2PP) and the sign in front of the Better PM term is negative. So, at least by the end of an election campaign, Better PM is just misleading fluff.

What About Between Elections?

Between elections there has been a strong relationship between Better PM lead and polled Government 2PP:

This is actually now slightly stronger than the relationship between PM net rating and government 2PP.

The relationship probably isn't quite linear; the 2PP is on average 0.4 points higher than the linear projection suggests for PPM lead values between -7 and +19. Even accounting for that, typically a government doesn't get to 50-50 2PP until its Prime Minister has a fourteen point lead as Better PM (seventeen points going off the linear projection), so all else being equal a Better PM lead any less than that is underwhelming in terms of what it predicts for the government's voting intention position at the time. A Better PM tie on average means the government is behind 47-53. Governments often recover from moderately bad polling, so a PM leading by, say, five points, is often in a recoverable position, but that's most likely just a fact about how voting intention changes rather than necessarily a fact about the pulling power of Better PM indicators.

But perhaps it might be the case that, say, a high Better PM lead for a given voting intention meant that voting intention was more likely to go up the next time? At the time of the previous article I noted that both PM net rating and Better PM do something called "Granger causing" voting intention, a finding that had just been noted for PM satisfaction and PM net satisfaction in Possum's The Primary Dynamic article.

This Granger-causation aspect has been taken as evidence that Prime Ministerial ratings (especially net satisfaction) are driving voting intentions, but the actual definition of Granger causality is merely that one time series contains information useful for predicting the future of the other. The definition doesn't say how it is useful, or in what direction. For instance, it might just be that the leadership scores preserve information that is lost from the 2PP because the 2PP operates in a narrower range and is hence more affected by rounding to whole numbers. When the 2PP is lower than would be expected based on a given leadership score, it is more likely to increase in the next poll, but this may just be because a 2PP that is lower than expected is more likely to be below 50, and 2PPs below 50 are more likely to increase next time rather than to get worse. I've made prolonged efforts to find a useful way in which Better PM and/or PM netsat tell us something useful about the future of 2PP voting intention polling, and found nothing.

And if we look at the cases where governments most out-performed expectations (1993, 2004, 2019) the Better PM histories in the lead-in are a very mixed bag. Paul Keating consistently underperformed on Better PM for a given 2PP against John Hewson in 1992-3. John Howard tended if anything to overperform against Mark Latham (even after adjusting for the preferencing issue), Scott Morrison was somewhere in between.

What about state data?

For state data I've used mainland states only, as Tasmania has normally had three-cornered Better Premier questions and uses Hare-Clark which isn't a 2PP system. I've excluded Queensland pre-1995 because of the three-cornered BPM issue and I've had to estimate a lot of poll 2PPs and the odd election 2PP especially in Queensland. Where Newspoll did not release a 2PP I have used the simplest method possible, which is a crude batched preference flow formula. In some cases using crude batched last-election preferences for poll 2PPs leads to irregular results, as there were a few 1980s state elections where non-major parties polled below 2% combined with their preferences appearing to split unnaturally strongly to one side (because the simple method I used did not take account of three-cornered Coalition contests.) For instance, this method puts the 2PP polling error in Victoria 1988 at around six points, when it was probably really around four. However, these issues don't stop the record of voting intention polling in predicting state results being quite impressive:

It may look from this that state Newspolls have been more accurate than federal Newspolls. In fact the average 2PP error in the state polls is larger (1.7 points vs 1.47 points) but because many state elections are not close, the percentage of variation in results that is explained by polling is higher. There has been a slight tendency for state governments to under-perform their final polling if it was strong for them, but not when it was weak.

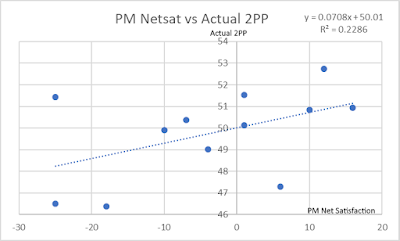

Looking at leadership ratings at state level they are much less predictive:

There is easily enough evidence to say that all of polled 2PP, Premier net satisfaction and Better Premier lead are correlated with the election 2PP. But a multiple regression finds that adding Premier netsat or Better Premier lead to polled 2PP does virtually nothing to increase predictive power. Final voting intention polling has predicted state election results in the past 35 years very well with rare exceptions - the leadership scores are just noise, and assuming they tell us anything we don't know from voting intention polling makes a prediction worse rather than better.

Also, Better Premier scores show a similar skew to Better Prime Minister. A Better Premier lead of zero translates to a 46-54 2PP deficit, which all else being equal is a heavy election loss. A Better Premier lead of sixteen points is needed before a state government gets an election-day 50-50 2PP on average. In contrast, Premier netsat is only very slightly skewed.

In terms of translating these indicators to election results:

* Governments leading in final 2PP polling have won 23 out of 28 elections while those trailing or even have won 4 out of 16. A government has about a 50% chance of winning at a polled 2PP of about 49.5%. (On election day, state governments have a 50% chance of winning at an election 2PP around 48.5% - thanks largely to South Australia.)

* Governments with a Premier leading as Better Premier have won 26 out of 36 elections, while those even or worse have won 1 out of 8 (Mike Rann, SA 2010, trailing as Better Premier by two points but won despite losing the 2PP decisively). A government has about a 50% chance of winning if the Premier leads as Better Premier by about 11 points.

* Governments with a Premier with a positive netsat have won 22 out of 26 elections while those with a negative or zero netsat have won 5 out of 18. A government has about a 50% chance of winning if the Premier's netsat is about -2.

Because of the skew, Better Premier lead is the worst predictor of the three - it gets 11 elections wrong compared to nine each for final 2PP polling and Premier netsat. Its recent success at federal level is largely down to luck - most of the elections were outside the window in which it is most likely to make mistakes, and in the two that were not (2007 and 2019, the former barely) it was saved by an unusually popular Opposition Leader and bad sampling, respectively. Based on the voting intention polling error in 2019, an accurate sample would have probably showed Scott Morrison with about a 25-point Better PM lead.

Why are Better Leader scores skewed?

Skew in these Better Leader scores exists across practically all pollsters who have polled them, but ReachTEL polls that force a choice between the two leaders have been less susceptible than others. I believe the problem is that the poll question is unsound because it presents the respondent with a choice between a devil they know and one they don't. It is similar to the choice faced by an employer who might consider sacking an employee and replacing them with another one. If the employer is reasonably happy with the employee they're likely to take an awful lot of convincing that somebody else - even who seems like a good choice - would do a better job. If the employer thinks the employee is just OK or maybe even a bit disappointing they might still be cautious about the idea of replacing them with an unknown quantity. Maybe they wouldn't back the incumbent, but they might take the "not sure" option instead. The incumbent has an advantage that they are Prime Minister so people know something about how good they are (or not) at the job. The opponent is usually an untried option.

Better Leader scores are a compound indicator that capture voter thoughts about the Prime Minister, the Government, the Opposition Leader and also how conservative the voters are or are not about a hypothetical switch to an untried commodity. There's simply no reason to believe these scores should be better at predicting how people will vote than a measure of how they actually intend to vote. The latter can be imperfect, as it was in 2019, but there's no evidence we can use Better PM scores to do any better.

Hi Kevin,

ReplyDeleteJust out of curiosity, I've tried modelling the Better PM score against the 2pp margin. While there isn't much of a relationship of the unadjusted score, when you perform the 16-point adjustment you mentioned in your previous post on the subject, there does seem to be something of a relationship at R^2 = 0.2838, which rises to 0.7098 if you ignore elections before 1996 (1993 being the failure of Keating vs Hewson).

However, even if you account for all the Better PM data, it does seem like this model of Better PM to 2pp does provide a degree of predictive value above the 2pp polls. Comparing the modelled 2pp from an average of Better PM scores a week out before the election to a similar average of 2pp results, it does seem like an average of Better PM-modelled 2pp and the polled 2pp would have done better in some recent elections than solely relying on the 2pp polls:

Election Better PM-modelled 2pp Polled 2pp Actual

2007 49.2 45.8 47.3

2010 49.2 48.7 49.9

2013 52.3 53.1 53.5

2016 50.5 50.4 50.3

2019 50.1 48.7 51.5

(apologies for the formatting)

Most noticeably, 2007 and 2019 stand out as results that could have been improved by accounting for the Better PM modelled 2pp. I don't have any polling data prior to 2007, so I can't be sure if this relationship holds, but might it be something worth looking into?

One reason Better PM might do better than the voting intention polls could be that it may be less subject to herding, given that there's no election result for it to be directly tested against and thus less pressure to "get it right".

Thanks for this comment. In my final-Newspolls dataset a model based off a linear regression of Better PM lead vs polled 2PP has a lower predictive error than the polled final 2PP (1.39 vs 1.47), so indeed the same thing applies, the Better PM model can help improve on the raw 2PP. However, it has a higher predictive error than ***a linear regression*** of final 2PP vs polled 2PP, which has an average error of 1.25. So when putting Better PM lead and final-poll 2PP on an equal footing (by doing a linear regression off each) the final-poll based model is so much the better predictor that even averaging it with a Better PM based model makes it slightly worse. Essentially the final-poll regression for federal Newspolls says that instead of taking the 2PP literally one should dilute it with about a 40% strength dose of 50-50. I suspect something similar would hold for aggregated polls as well - it certainly would on your figures for 2007, 2010, 2019. I've edited the text in a few places to explain that the best of the 2PP-based predictions is not the polled 2PP but a model based off it.

DeleteConcerning 2007, aggregates that do not weight heavily by date of release in the final days for that election are blown off course by Nielsen's final 57-43 (with Rudd ahead 52-40 as preferred PM), and also I'd expect by pre-final polls from other pollsters. In 2007 there seems to have been a swing back to the Coalition in the final days, probably as voters realised Labor was going to win and decided to save their local Coalition MP, ensure an effective Opposition or whatever. Nielsen, who probably also had some bad luck with sample noise in their final poll, were punished for coming out of field three days before election day and were outperformed by final polls that came out later - Newspoll and Galaxy 52 and Morgan 53.5.

Concerning 2019 I'd expect models projecting off Better PM to do better than models projecting off the herded set of polled 2PPs, and this is also the case for my final-Newspolls based model (49.6 vs 49.2).

I also find that if I throw 1993 and before out of the sample, then the R^2 for the better PM based regression improves to slightly above the R^2 for the equivalent 2PP-polling based regression. (I get 0.5882 vs 0.5249 - adjusting the BPM scores by adding a constant shouldn't make any difference.) In the final-Newspoll sample the years when the 2PP-based regression most outperforms the Better PM based regression are 1993, 1996 and 2013 (also modestly in 1990), with the Better PM based regression outperforming the 2PP based one to a lesser degree in all of 1987, 1996, 2001, 2007 and 2019.

I mainly just used Newspoll because Newspoll better PM is the subject of dozens of times more hype than everybody else's put together, but there are also a lot of issues with using other pollsters because of the constantly changing pollster mix and the different answer format in ReachTEL specifically.